#14 shillings 6 pence

Text

Remember, an elephant is not just for Christmas!

If you are a medieval ruler like Henry III who received an elephant from his brother-in-law (St) Louis IX of France in early December 1254, be prepared to spend:

£6 17 shillings 5 pence (refund to the sheriff of Kent for transporting the elephant from France to England)

£22 20 pence on a multi-purpose elephant house at the Tower of London

£24 14 shillings 3½ pence on food for the elephant every nine months

By comparison, a laborer might earn just 1-and-a-half pence per day, while a well-to-do knight might live on £15 per year. (For more, see Cassidy's and Clasby's article from the Fine Rolls of Henry III Project.) And don't forget, you will have to pay for the elephant's keeper, too! The monk-chronicler Matthew Paris helpfully depicted Henry III's elephants alongside one of its keepers for scale. The man is labelled as Henry de Flor, "mag[iste]r bestie" ("caretaker of the beast").

Sadly, Henry did not have these expenses for long: although many medieval legends emphasized elephants' longevity, this elephant only lived until 1257 in the inhospitable northern climate. When it died, it was initially buried in the tower, but Henry later had its bones transferred to Westminster Abbey.

Despite these difficulties and costs, elephants had a notable history as diplomatic gifts in the Middle Ages, even in regions where elephants did not naturally live. Charlemagne's elephant Abul Abbas is a very early example of the phenomenon, and by the eleventh century Byzantine emperors were receiving elephants in Constantinople. In 1228, the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II received an elephant from al-Kamil, the ruler of Egypt, and King Louis IX probably also received his elephant from an Egyptian ruler before regifting it to Henry III.

Side note: although the "white elephant" gift exchange claims to be based on a southeast Asian ruler's practice of punishing courtiers with a gift that would cost them a lot of money, there is not much historical evidence for this before the story was shared in the Anglo-American world in modern era.

Some elephants fought back over being passed around as gifts, though. In the early 15th century an elephant and other rare animals arrived in Japan. (Martha Chaiklin has suggested that they were intended as a diplomatic gift for someone else, but were blown off course and ended up with the Ashikaga shogun.) The elephant was extremely grumpy and trampled some courtiers, so the shogun regifted it to Taejong, ruler of Korea. The elephant continued to trample courtiers in Korea and was expensive to feed, so Taejong exiled it to its own private island, where it continued to live.

Materials: parchment, ink, and pigments

Contents: Matthew Paris's Chronica Maiora

Origin: St Albans Abbey (made by the scribe-illuminator-chronicler-monk Matthew Paris)

Now Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 16 I, f. ii r

#elephant#elephants#medieval elephants#illuminated manuscript#13th century#medieval#elephants as gifts#unique gifts#medieval gifts#global middle ages#diplomacy

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

February 14, 1809

Slept one sound nap from 12 to 9! What has happened to make me such a sluggard? It must be the air of this country. They all sleep. My habits are as temperate as you have heretofore known and yet I absolutely require seven hours sleep. Whence this strange revolution ? Madame Prevost is extremely attentive—Un air d’elegance et d’abbatement¹. Peutetre 28². While I was at breakfast, J.B. and K. came in; a quiet laugh; brought me letter from Meeker proposing an interview and advising that he will leave town this evening for eight days. Cannot find Grandpré. Note from General Hope about packets. Message from Castella that Grandpré is here but his address denied at the Alien Office. Message from Colonel A.C.J. requesting an interview at 12 this day at Q. S.P. Sor. at 12. To Q.S.P.; waited till 1/2 p. 1. A.C.J. came not. To D.M.R.’s; out; left there my great coat, being too warm. To Green street cabinet-maker for chess-table. To L. Duval’s, 4 New Square, Lincoln Inn; there received answer from Mr. England giving address of M’K.—Binfield, Berks; his father lying dead there. Answer from Humphrey; he had had no further communication with T. or W., and asks my “determination.” Wrote him reminding him of the determination already made known to him. To Meeker’s, 14 King street, Holborn; gone. To D.M.R.’s, whom found waiting for me; sent out for mutton and potatoes, and staid till 7. Returning home, corsettiere. Bru. che. noi. bo. su.³; 7 shillings. Drink, 1 shilling 6 pence. Fruit and chestnuts for Madame P., 2 shillings. Carpet for the foot-board of O.'s chess-table, 2 shillings. To Q.S.P. at 1/2 p. 8. Sat 1/2 hour; refused tea. Home at 9. Madame P. not yet come in. Mais bientot venoit⁴. Foreseeing that we might go the round of sentiment, though I think we shall go rapidly through it, thought it necessary to coo dow. Ce pung. l corsettiere⁵. An hour with Madame P. La 2 lecon car. et souprs⁶. Des progres; ca je finira en deux jours⁷. Two hours arranging papers, noting down and arranging names. Took tea seul at 10. Couche at 1/2 p. 10, having lost 2 1/2 hours with P. Des progr. rapides⁸.

1 An air of elegance and dejection.

2 For peut-etre 28. Perhaps 28.

3 For corsetière. Brunette. Cheveux noirs. Bon sujet. Corset-maker. Brunette; black hair; good subject.

4 But she came soon.

5 This is a great riddle. Possibly meant for: Thought it necessary to kotow (formerly spelled kootoo and various other ways); cependant la corsetière. It would then mean: Thought it necessary to bow, i.e., say good-by, in the meantime, to the corset-maker. (The word kotow, introduced into English from China, was used in England even before Burr's visit there.)

6 For la deuxième leçon [des] caresses et [des] soupirs. The second lesson consists of caresses and sighs.

7 Progress. I’ll finish that in two days. (Finirai.)

8 For Des progrès rapides. Rapid progress.

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

bro,,,, do you remember me,,,, 14-shillings-and-6-pence,,,

OH MY GOD?? YOURE ALIVE DUDE???

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

I love you 🥰

🥺🥺🥺🥺💖💖💖💖 I love you too, Alex!!

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

when you see a gun, grab sword, not pp

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Bro I don’t know what your blog names means but let me just tell you- I like it

Oh! Allow me to give you backstory no one wanted--

Basically, long story short, Aaron Burr spent 14 shillings and 6 pence on a coconut, which is about the equivalent of $400 U.S. so I just snatched it up--

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Burr’s Strange Fruit, A Followup

xinea replied to your post “A coconut for 14 shillings 6 pence?”

https://books.google.com/books?id=qVkDAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA311&lpg=PA311&dq=aaron+burr+jh&source=bl&ots=l7eZzgQKJ5&sig=jpH-4hH7Vo67lkM6YfBvlSiTYOc&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0CCkQ6AEwAmoVChMIjrvKo4TByAIVyzc-Ch2V6goE#v=onepage&q=ass&f=false

to be fair he also bought oranges and dates?

Excellent, we now have sources! now I know I should have started with his diary! (To be fair, I was on mobile.) Thanks, @xinea!

#xinea#aaron burr#14 shillings 6 pence#coconut#aaron burr's coconut#sorry for the late reply#finally managed to get to use the desktop#replies

1 note

·

View note

Text

.:£/d:.

~,~,~,~,~,~,~,~,~,~,~,~

the LSD system.... but there is a monetary unit for every single factor of 240.

i think this would be the perfect system.

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, 16, 20, 24, 30, 40, 48, 60, 80, 120, 240

and also all the numbers in between them, so long as they are divisible by 2, 3, 5, or anyother number in the above list. but those only for special coins. commemorative coins, ‘n that. and it should all be based on precious metals ofc.

ive been drawing up charts about this btw.

(and im only talking in pence right now.)

((but remenber, 12 pence in 1 shilling, 20 shillings in 1 pound =:. 240 pence in 1 pound))

𝔰o:-

~.~.~.~

9,` 14,` 18,` 21, 22,` 26, 27, 28,` 30,` 32,` 33, 34, 35, 36,` 38, 39, 40,` 42,` 44, 45, 46,` 48, 49, 50, 51, 52,` 54, 55, 56, 57, 58,` 60,` 62, 63, 64, 65, 66,` 68, 69, 70,` 72,` 74, 75, 76,* 78,` 80, 81, 82,` 84, 85, 86, 87, 88,` 90,* 92, 93, 94, 95, 96,` 98, 99, 100,` 102,` 104, 105, 106,` 108,` 110, 111, 112,` 114, 115, 116, 117, 118,* 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126,` 129, 130,` 132,* 134, 135, 136,` 138,` 140, 141, 142,* 144, 145, 146, 147, 148,` 150,` ---152, 153, 154, 155, 156,` 158, 159, 160,* 162,` 164, 165, 166,` 168,* 170, 171, 172,` 174, 175, 176, 177, 178,` 180,` 182, 183, 184, 185, 186,* 188, 189, 190,` 192,` 194, 195, 196,` 198,` 200, 201, 202,* 204, 205, 206, 207, 208,* 210,` 212, 213, 214, 215, 216,* 218, 219, 220,* 222,` 224, 225, 226,` 228,` 230, 231, 232,` 234, 235, 236, 237, 238,`

a coin or note for each of these, but these are special denominations.

all divisible into tuppence, thruppence, groats, sixpence, shillings or pounds. and all the rest.

but not:

7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 25, 29...

no coins for these.

wait... these are just primes

Good Lord. thats it, isnt it.

a coin minted in every denomination, using the magic number of 240, but no coins minted in primes. (except 2, 3, & 5.... of course.... and 1. but they say 1 isnt a prime, even though he’s the first. hmm. but not the number 77, or 91, or 119, 133, 143, 161, 169, 187, 203, 209, 217, & 221 [= *] --- because those are only divisible by primes, -{7, 11, 13}- let it be known::~~more research needed/)

primes:=

2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37, 41, 43, 47, 53, 59, 61, 67, 71, 73, 79, 83, 89, 97, 101, 103, 107, 109, 113, 127, 131, 137, 139, 149, 151, 157, 163, 167, 173, 179, 181, 191, 193, 197, 199, 211, 223, 227, 229, 233, 239 :=? `, ``, ```, ```’, ```’`,```’``

so this could keep the decimal system, because 10 is a divisor of 240. keep the 5p and 10p, but rework them into the new imperial system, it would be the ideal way. tell me im wrong.

PS:-rough draft, may contain mistakes; reblog at your own peril.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

How much did “Chintz” or “Calico” cottons cost in the 18th Century?

In this century, when we think of “calico” we more than likely envision a cotton with a small print a la Little House on the Prairie, but calico in the 18th century was just a name for printed cottons and had nothing to do with a specific pattern or design.

It’s interesting to note just “how” printed fabrics were accomplished. A wood carver would create a wooden block of a pattern - such as a cluster of flowers, etc. That block or “stamp” would then be brushed with mordant to make the dye adhere to the fabric. The artisan would then stamp the design on the fabric, then dye the whole piece. It would then be rinsed to reveal the stamped design.

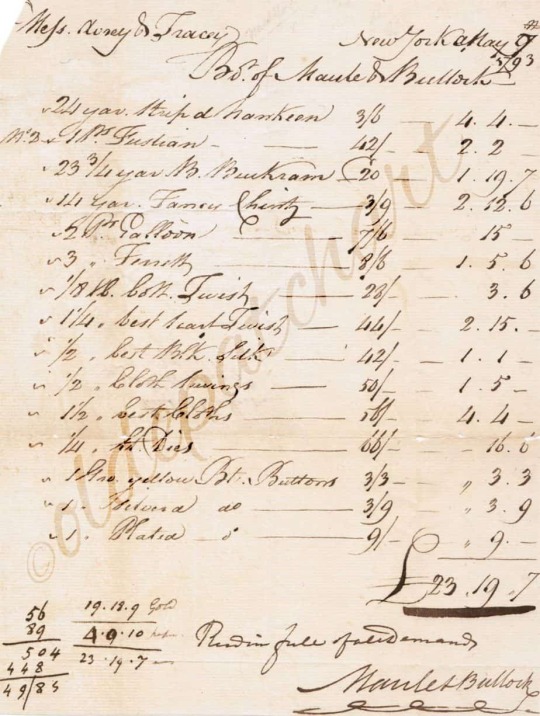

Attached is a copy of a bill of goods from New York dated 1793. I needed to know how much a yard of printed cotton would cost for one of my novels that is set in 1773. As a writer, research of such minutiae is par for the course, but as a costumer I was doubly curious.

“Chintz” was a type of printed cotton produced in India, The Calico Acts (1700, 1721) banned the import of most cotton textiles into England, followed by the restriction of sale of most cotton textiles. It was a form of economic protectionism, largely in response to India (particularly Bengal), which dominated world cotton textile markets at the time. Parliament began to see a decline in domestic textile sales, and an increase in imported textiles from places like China and India. Seeing the East India Company and their textile importation as a threat to domestic textile businesses, Parliament passed the Calico Acts as an attack on textile importation. This is the same reasoning Elizabeth-1 enacted sumptuary statutes on “black dyed woolen hats.” But I leave that topic for another time! The point being is that protecting English trade by banning certain imports was not a new device.

During the 18th century the monetary system in the colonies was in pounds shilling and pence. There were 20 Shillings to the pound and 12 Pence per Shilling. Also at the same time each colony had their own currency system. For instance the New York pound was worth 30% less than British sterling, with a NY shilling equivalent to only 8 pence sterling instead of the usual 12. Among the list of goods purchased on the 7th of May 1793 according to the bill of sale pictured, is a 14 x yards length of ‘Fancy Chintz’. It cost 3 shillings 9 pence per yard with the total cost coming to two pounds, twelve shillings and 6 pence.

Now, do not quote me as an expert. I’ve drawn my information from several on-line sources and it’s been suggested that these prices are very likely listed at wholesale, or purchased for “cost,” as the buyers themselves were merchants and would mark it up to make a profit.

Let’s consider wages in the time period of 1773 thereabouts. According to what I’ve been able to source on-line, the average wage for a farmer would be about 10 pounds per year. A day laborer, or farm hand, would make about 6 shillings per month. When you work out the comparison using wages of each era and try to calculate how much ONE yard of chintz would cost, it appears that it was equivalent to approximately three quarters of a day’s wage (in 1793).

Depending on the width of the fabric a typical round gown, which is a gown that isn’t split up the front and worn with a decorative petticoat, would take about 6 yards or more. I’m making that estimate based on what “I” would purchase for a textile that is 45" wide. That means the cost of ONE gown would equal to about a week’s wages! HOLY COW!

For us in 2021, cotton is an inexpensive textile. A polished cotton or chintz now days costs about $20 a yard. The brown and ivory fabric I used in the recent gown I shared cost about $19 a yard because it was a historical reproduction, but on average printed cottons cost about $10 a yard, while wool fetches a price of anywhere from $25 to $40 a yard! In the 18th century wool would have been much more affordable than cotton chintz or calico.

I’ve included some of my FAVORITE cotton prints that I’m anxious to have an opportunity to use on a robe a’ la polonaise! They are ALL available on Spoonflower. They are NOT historical reproductions, but… close enough to pass some prints from the 18th Century.

You can view my full “collection” of cotton prints on my Pinterest page:https://www.pinterest.com/…/cotton-prints-historical…/

A blog I used for reference: https://oldepatchart.com.au/…/11/18/yard-chintz-cost-1793/

Other sources were found on a Google search.

#18th century fashion#18th Century#historical fashion#historical costume#historical film#periodcostume#colonial williamsburg#costume design#costume designer#artists on etsy#etsyhandmade#etsylove#etsyfinds#etsymaker

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aaron Burr and his umbrella misfortunes

Home at 4. Caught in the rain, having yesterday left my umbrella at Brentford—no doubt lost. Dinner, B. and K. Read out the review of the "Life of Washington" by Marshall and Ramsay. The review is full as stupid, and as illy written, as either of the books.

- December 6, 1808

Loses umbrella for the first time. (Bonus throwing shade on Life of Washington and its review.)

Rose at ten. Such is the mode in London. Sor. at 1. Going up Haymarket, met Madame O., and walked with her half an hour. Went to the stage-house in Piccadilly to inquire for my umbrella, but with little hope. It was there, brought by the coachman; 1 shilling 6 pence. How very honest people are here, and yet I am cheated most impudently every hour!

- December 7, 1808

Finds the umbrella, has to pay to get it back.

Rose at 6. Set off at 7. I sleep very soundly in these stage coaches. By sleeping, however, forgot to ask for my umbrella, which I had left at Stanmore.

- December 14, 1808

When he seemingly forgets it again.

Stayed to dinner. Out at 10; raining, took K.'s umbrella, having lost my own. Koe overtook me, having run all that way in the rain; sent by Bentham to bring me back to sleep, he not suspecting that I was going off. Apologized.

- February 8, 1808

And again.

As I was writing the concluding line of the preceding page last evening (about 1 o'clock) an ill-looking fellow opened my door without knocking, and muttering in German something which I did not comprehend, bid me put out my candle. Being in no very placid humor at the moment, as you see, I cursed him and sent him to hell in French and English. He advanced and was going to seize the candle. My umbrella, which had a dirk in the handle, being near me, I seized it, drew the dirk, and drove him out of the room. Some minutes after I heard the steps of a number of men and looking out at my windows saw it was a corporal's guard. It then occurred to me that this Erfurt, being a garrison town with a French governor (de Vismes), there might probably enough be an order for extinguishing lights at a certain hour, and I had no doubt but the gentlemen I had just seen in the street were coming to invite me to take a walk with them. So I bundled up my papers and put them in my pocket to be ready for a lodging in the guard house. It was only the relief of the centinels' going round and who the impertinent extinguisher was I have not learnt.

- January 9, 1810

So much to unpack here I don’t know where to even start. I don’t know if my favourite thing is

that there was a stranger barging into his room insisting he puts out the candle,

that he crankily attacked him with a knife,

that the knife was hidden inside the handle of his umbrella,

that he suddenly remembered there was a law forbidding light after a certain hour

and was afraid the guards passing by might be coming for him

...or that he had a rare stroke of luck and nothing happened

Sor. 11 to the umbrella-mender; nothing done.

- April 20, 1810

I had no paraplui² and was resolved not to take coach if one had offered. Got home wet to the skin, from head to foot. Jul. made me a good fire, for my chimney was reformed a little. Changed clothes. Caf. blanc, and am quite refreshed.

2 For farafluit. Umbrella.

- October 18, 1810

Deliberating on the state of my finances, found that this sans sous state was not only inconvenient, but dangerous; for instance, this morning I hit a glass window with my umbrella, and had nearly forced it through one of three large panes. In such a case you have only to pay, and there's an end of it; but had I broken the pane and not been able to pay for it, I must infallibly have been taken before a commissionaire de police to abide his judgment.

- December 10, 1810

Burr what were you doing

Thence to Vanderlyn's to get more newspapers. While there it set in to rain; had no umbrella, and got wet.

- December 12, 1811

A brilliant morning. Sun shining bright for this hemisphere. Went out without my umbrella. Before I got one hundred yards it began to rain. Went back for the umbrella.

- February 13, 1811

At least you went back for it this time I guess?

Very grave and philosophical, and full of good resolutions. Have lost my umbrella! But it is better to begin in the usual form.

- February 18, 1811

Had breakfast at 6. Was sitting in the parlor below reading a newspaper. Received a smart click on the head. It was Madame. "Mais vous etes la tout tranquille. Vous laissez tous vos hardes pele mele. Voila votre paraplui. Vous ne pensez a rien. Vous etes come un enfant. Le diligence va partir et vous ne faites rien"².

2 For "Mais vous êtes là tout tranquille. Vous laissez toutes vos hardes pêle-mêle. Voilà votre parapluie. Vous ne pensez à rien. Vous êtes comme un enfant. Le diligence va partir et vous ne faites rien." "But you are quite at your ease there. You leave all your clothes lying pell mell. There is your umbrella. You don'tthink of anything. You are like a child. The diligence is going to leave you and you are doing nothing."

- May 18, 1811

After the fireworks were done, Mr. L. proposed that he and I should walk along the river and about the palace, to see the various illuminations. F. recommended this; we saw her in the carriage, and she went off; we were to take our chance for a hack. Mr. L., not being well acquainted with the ground, and the confusion produced by the variety of light, led us astray, and when we reached the river found ourselves 1/2 mile above the bridge. It now began to rain hard; we had no surtouts or umbrellas. When we reached the bridge, there was nothing to be seen which we had not before seen from a better point of view. We, therefore, took shelter in the first house we could get in ; but the crowd was so immense that even this was difficult. At length we had room to stand up under cover. Mr. L. then went out to hunt a carriage. All were engaged. He went in another direction, and, after an hour, returned without success. He was not to be discouraged. Out he went again. A guinea was asked for a seat to town, about six or seven miles; and then you must be crammed in with six or eight drenched people. At 1/2 p. 1 he returned with a carriage; at what price I know not, for he would not let me interfere.

- June 23, 1811

I should say this was the same day as, or shall I say directly after the “got brain freeze and thought he was dying” episode. Burr just can’t catch a damn break.

The chevalier led me au P. R., after strolling an hour, in a caffe into a cellar, which I will describe as well as I can. We took ice-creams. There was music and a ventriloquist. We agreed to neglect Madame F. At 1/2 p. 10 I got home.

[...]

Mem.: Left my new umbrella at that confounded ventriloquist's and am sure shall never see it again.

- June 30, 1811

My umbrella is lost; lost 32 francs. Paid for our ice-creams 3 francs.

- July 1, 1811

To near Luxembourg 5 to get an umbrella which some one, unknown, left in my room a fortnight ago, and which has, therefore, become my property by prescription. Paid for mending it, 3 francs.

- July 11, 1811

Score! Gains an umbrella instead of losing it for once.

The morning appearing fine, went out without my umbrella and got well wetted. It is against my conscience, you know, to hire a hack.

- January 29, 1812

Set out for Lincoln's Inn Fields, but hard rain coming on, and having taken no umbrella, the morning being fine, turned about and stopped a few minutes at Godwin's. Continued in all the rain; by musing, lost my way and got wet to the skin. Home at 4. Changed and made a great fire.

- January 30, 1812

Burr. Burr.

And here is where the fun begins:

Got home at 4, and discovered that I had lost my umbrella; a most serious misfortune, and little hope of recovering it, as I have no recollection where I stopped. It is impossible for me to buy one or to do without one.

- February 18, 1812

Slept near seven hours last night, and did not rise till 8. My umbrella hung heavy at my heart. Went to hunt for it. Walked back on the track I came from J. H.'s yesterday, and called at the places I had been; but no umbrella. It is finally lost, and I must submit to the inconvenience of getting wet and of spoiling my clothes.

- February 19, 1812

Then home, following again the track of my poor lost umbrella, but to no purpose.

- February 20, 1812

I had intended to have breakfasted at J. B.'s, for the purpose of taking the retorts early to friend Allen; but in the first place I slept till 9, and in the next it rained in torrents and you know my umbrella is on a voyage.

[...]

The rain setting in again, bought me the cheapest umbrella I could find that was large enough. Cost 10 shillings and 6 pence.

- March 2, 1812

THE END.

#because someone had to do it#Aaron Burr#and the umbrella#amrev#the history peeps#thp#long post#own post

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

February 12, 1809

Lev. at 10. Sor. at 1/2 p. 11. To D.M.R.; had just gone out to call on me; got lost an hour. To Vickery’s, where got peruke. To Duval’s; out and all locked up. To W.R.M.; out; wrote in his room a note requesting to appoint a place and time of interview and to enquire about Grandpré mentioned in previous letter as having come out in November with letter for me from Min. and E.A. To Mr. Duval’s, 44 Great Russell street, where wrote note to Lewis D. desiring him to get M’K.’s address from Mr. England, his attorney. To Castella’s, Fitzroy square; saw him and his two nieces. He walked with me to Charles Smith's, 14 Beaumont Place. Charged Castella to inquire for Grandpré. Smith out; left his brother's letter and card. To Cochrane Johnstone’s, 13 Alsop’s buildings, New Road; out. Returning, took coach and drove to Surrey street, Mrs. Hick’s. Gamp tired. Message from Galley. Marriage of Miss Chase. Home at 1/2 p. 4 in coach; 4 shillings 6 pence. Dinner with J.B. and K. At 6 began to pack up for removal. To Anna; 7 shillings. Porter to take my things to Charing Cross; there took coach. To D.M.R.; out. To 2S James street. Porter, 3 shillings; coach, 3 shillings. Madame ———, d’ou diab.vient elle¹? Sent by the Devil to scd.² Gamp. Set to unpacking and stowing away, which with smoking and idling and thinking about writing, kept me up till 2. How many beautiful letters I should write were it not for the mechanical labour of writing, which I hate!

1 For d’où diable vient-elle? Where in the devil does she come from?

2 For seduce.

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Bruh smh why did you not answer my epic Aaron Burr ferret headcanon? 🥺

Bro I'm so sorry it got buried under like 50 asks I'm so sorry :(((

But also you're very right. Very right.

Also remember how I said Jefferson has ferrets??? Yes he got them because Burr had them and he thought "wOAH THEYRE COOL"

#hamilton#hamilton: an american musical#aaron burr#headcannon#headcannons#thomas Jefferson#ask#answer#ee answers#ee talks#ee.txt#14 shillings and 6 pence

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey all sorry if you get tagged but I'd like some help please

My mom said if I give her 25 good reasons she might let me shave my eyebrows off (I've wanted to do this for almost two years now)

So could y'all help me come up with some?

@yo-whaddup-my-bros @thelargeshook @overenthusiasticbookworm @vapingavocados @revolutionary-romanticv @rolofilledheadphones @14-shillings-and-6-pence @homosexual-dino @kindawannadietbh again so sorry for the tags but y'all are most of the people I trust there are more but that's what I can think of right now so please

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

@14-shillings-and-6-pence is a hoe and @feral-enby isn’t

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Popularization Of Tea in England

The [British East India] company established a “factory,” the trading post of a factor, or agent, in Canton in 1699, and later merchants from other countries did the same. Company ships had already begun to take part in the so-called junk (or country) trade with Southeast Asia (“junk” is a Malayan word for ship), conducted by Chinese merchants and operating out of Ningpo, Xiamen (Amoy), and Canton. Canton soon became the chief entrepôt for the English trade, which dealt in such articles as silk, porcelain, lacquer, fans, rhubarb, musk, and “tutenag,” an alloy similar to zinc. Before long, however, tea became the principal article of trade, and the demand in England rose steeply. In spite of conservative objections to this new and insidious drink, the popularity of tea did much to deliver the lower classes in Britain from the use of cheap gin, whose harmful effects are so vividly displayed in Hogarth’s prints.

The figure for tea exports to Europe in 1720 was about 12,700 chests per annum, the major amount going to the London market. A marked increase took place between 1760 and 1770, and by 1830 the figure had reached 360,000 chests a year. In 1803 the tea imported into England was worth over £14 million sterling. Dr. Samuel Johnson must have been in the forefront of those who popularized the drinking of tea, for Boswell remarks, “I suppose no person ever enjoyed with more relish the infusion of that fragrant leaf than Johnson. The quantities which he drank of it at all hours were so great, that his nerves must have been uncommonly strong not to have been extremely relaxed by such an intemperate use of it.” The year was 1756.

...

The better brands, Congou and Souchong, were sold wholesale in London in about 1800 for 2 shillings 10 pence to 6 shillings 10 pence per pound, but the most expensive teas would retail at 16 to 18 shillings per pound. The high value of tea serves to explain its careful storage in beautifully made tea caddies of hardwood with elaborate brass locks. The common people were also able to afford tea in small quantities of a brand known as Bohea, selling for less than 2 shillings 6 pence a pound, in which tea leaves were mixed with some leaves from other plants, such as sloe, liquorice, or even ash and elder.

(China, Its History And Culture, W. Morton)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

@14-shillings-and-6-pence is now officially my father

26 notes

·

View notes