An evolution based research blog by Jess Cowie-Kramer at the University of Northern Colorado

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Obstetric Dilemma

May 5, 2023

Ask any mother and she will tell you how intimidating birth can be. So many things can go wrong (and it hurts).

This has been true for most of history. Giving birth can be a scary process. The human body was not originally designed to be walking upright, and our birthing evolution has not quite caught up with how the body has changed. Maternal mortality is a huge concern and has been historically. Maternal mortality rates average at 8 deaths per 100,000 live births in the European Union; even going as low as 3-4 per 100,000 in some countries. Other developing nations have a much higher rate. For example, in Sierra Leone, a woman is 300-400 times more likely to die than in the European Union with a rate of 1,360 deaths per 100,000. (If you’re interested in disparities in healthcare as it pertains to maternal mortality, check out this website.)

Although maternal mortality rates are much lower today than they have been in the past, they are still higher than that of other primates. Scientists think that there are two main reasons why humans differ: increased infant head size due to the evolution of larger brain volume and changes in the anatomy of the female pelvis in response to bipedalism.

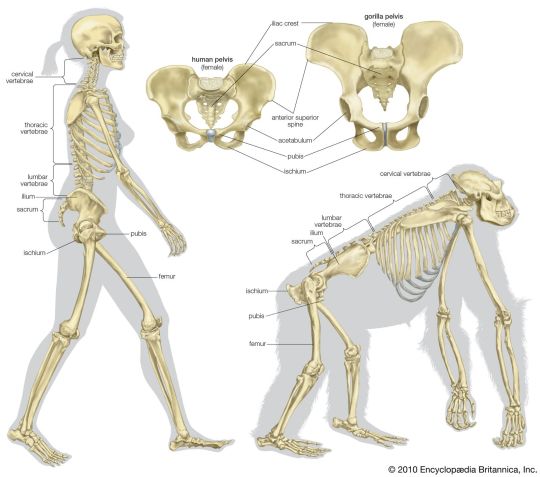

Obviously, as homo sapiens, we walk upright on two legs. Most other primates do not share our bipedalism. Millions of years ago, we were just like them and walked on four legs. There are several theories why homo sapiens evolved to walk on two legs instead of four, but that is a discussion for another time. We are focusing specifically on how the anatomical changes associated with bipedalism affects maternal mortality. In order to walk upright, some changes had to be made. The pelvis changed shape to allow the lower limbs, knees, and feet under the body's center of gravity. These changes allowed our ancestors to balance on one leg while moving the other to take a step. Feet evolved from being flat and good for climbing trees to having arches good for running. The skull and spine also underwent morphological changes so that the skull would sit directly on top of the spine for better balance (seen in the image below).

Humans have a larger brain volume compared to other species. We also have a larger brain to body ratio. This is fantastic for learning how to use tools, agriculture, and building civilizations, but not super great when an infant’s large head must fit through a mother’s pelvis. Traditionally, primates have wide birth canals with an angle that allows for easier childbirth. As discussed above, the pelvis changed morphologically in response to walking upright. the birth canal became narrower as a result. Simultaneously, as humans evolved larger brains, they evolved larger skulls to match. Obviously, this poses an issue between smaller birth canals and larger heads and is referred to as the obstetric dilemma.

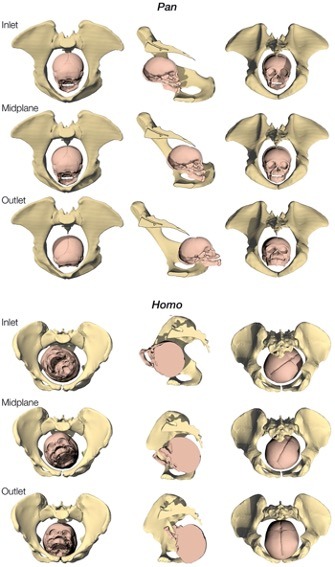

The diagram below demonstrates the differences in how a chimpanzee’s head fits through the birth canal vs a human's. As you can see, the chimpanzee’s pelvis is wider and the head passes through easier than the human’s.

Changes in pelvic structure also have to do with thermal regulation of the body. People living in higher, colder latitudes have shorter, wider torsos to conserve body heat. This also changes the anatomy of their pelvis to be wider than those who live in tropical areas. Consequently, this leads to pelvic differences between ethnic groups. Mortality rates could be improved if morphological differences between these groups were taken into account.

Scientists hypothesize that there have been certain evolutionary trade-offs to compensate for this problem. Homo sapien infants are born relatively undeveloped compared to other mammals. We can see this in how long we spend with our mothers and our lack of ability to walk at birth. Potentially, this immaturity in development means that babies skulls are smaller at birth. Their skulls are also not fully formed. Everyone who has held a baby knows that you must be particularly careful with their heads since they have fontanelles, or gaps where their bones have not fused in their skull (as pictured below).

Overall, the obstetric dilemma still poses a threat to mothers around the world. We do have some modern workarounds to it (like a C-section), but natural childbirth is still a concern. I was inspired to write this post after reading an article about maternal mortality. I wondered why humans have been able to reproduce so well that we now have 8 billion people on this planet. One reason we’ve stuck around this long, despite the obstetric dilemma, is that mothers who had narrow birth canals that were unsuitable for birth have already died in childbirth along with their baby, and therefore did not pass on their genes. Survival of the fittest can be brutal.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abracadabra, Populus tremuloides!

March 30, 2023

Temperate forests are often overlooked in terms of interest. Tropical rain forests usually catch the attention due to their impressive biodiversity of species and brightly colored flora and fauna. But temperate forests have their own special magic. Trees change their colors in the fall, lose leaves in winter, and appear to come alive again with spring blossoms. In this post, I hope to convince you that temperate forests hold their own magic by describing the aspen tree.

Aspen belong to the genus Populus. The species we in Colorado are most familiar with is Populus tremuloides, or the quaking aspen. It is named for how the round leaves shake and quake in the wind. Their bark is often white or pale yellow/green in color. The bark contains chlorophyll so when the trees shed their leaves in the winter, they are still able to perform photosynthesis. The leaves will turn bright yellow/gold in the fall. Aspen have evolved to reabsorb the chlorophyll from leaves back into their bark so that they are able to conserve resources and energy to survive the winter. This reabsorption produces that famous golden color.

Trees belonging to the Populus genus are both allopatric and sympatric. Some exist in the same location as their own little neighborhood. There are also many neighborhoods of these trees. If you’ve gone hiking in Colorado, especially in the fall, you can see yellow patches of leaves against the dark green coniferous trees. Those yellow leaves often belong to aspen, demonstrating how they occupy their own area in the forest. In the table below, I have included other species of the Populus genus so you can see how far they have spread. Aspen and polars are suitable for many environments. They are able to grow in many conditions: “moist streamsides, to dry ridges, on talus slopes, in shallow to deep soils of various origins, and is tolerant of wide variations in climate. It is found in all mountain vegetational zones, from the basal plains of the mountains to the alpine. As a result, aspen communities are found associated with a diverse range of vegetation, from semi-arid shrublands to wet, spruce-fir forest.”

Aspen play an important ecological role. They are considered a keystone species by playing a role in primary succession after natural disasters and providing habitats for other organisms to live. Aspen groves contain the second greatest biodiversity in the ecosystem besides riparian areas.

Aspen trees can reproduce in two different ways: the more traditional flower pollination route or by creating clones via asexual reproduction. Clones are more common than pollination. Seeds created by the aspen are only viable for a short time and they are greatly impacted by weather. The aspen seeds are delicate and often do not survive. This presents an isolation barrier for the trees. Clones are genetically identical to the parent tree which limits biodiversity. Due to clones being a more favorable reproductive strategy, many aspen groves are actually just a single tree or a few trees. Clones of aspen, or ramets, contribute to how hardy this tree is. If an off shoot from the original parent plant is separated from the shared root system, it will become its own tree and survive independently. Often, a single clone can be more than one acre, connected by underground root systems.

The largest clone on record is 100 acres in size. He (since aspen are diecious and can be male or female) is referred to as Pando or the Trembling Giant. And you can see part of him pictured above! Pando has been aged at 80,000 years old and weighs over 14 million pounds. Unfortunately, due to humans and our poisoning of the planet, Pando hasn’t grown for several decades. Researchers think that overgrazing by herbivores, drought, and fire suppression may be contributing to this slow death of the Trembling Giant. Efforts are underway to save this giant.

Hopefully, this post informed you of some temperate forest magic. There are more cool trees besides those found in tropical rainforests. Aspen and their beautifully colored clones are proof of that.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Convergent brains and octopi- oh my!

February 23, 2023

If you’ve been on the internet in the last few years, you may have seen viral articles and videos about an octopus escaping its tank and getting out to sea, solving mazes, or opening jars with lids. They are very intelligent creatures, despite being invertebrates.

The octopus belongs to the Cephalopoda class in the phylum Mollusca. (Fun fact: cephalopod means "head foot") Other species in their mollusk family such as snails, mussels, and slugs do not share the same advanced centralized nervous system. The octopus has been said to have nine brains; one central brain and one smaller brain per each of their eight arms. Technically, the “brains” in their arms are ganglia, or bunches of neurons close together. These little brains can touch, taste, and smell. Each arm can operate semi-independently without input from the central nervous system. When surgically removed, an arm can still do basic movements.

Octopi share similar brain to body ratios to mammals despite not being closely related. However, they do share a common ancestor, probably a simple worm with a simple nervous system. That ancestor gave rise to two lineages: the chordates with a central nerve cord and brain, and others with bunches of ganglia connected across the body. The octopus falls into the second category. But they evolved further. Their ganglia became centralized, very similar to chordates.

Development of similar structures despite distant relation is referred to as convergent evolution. Some ideas are so good, evolutionarily speaking, that they essentially evolve twice. Having a larger brain allows for more sensation, finer motor control, and better memory. The nervous systems of an octopus and mammals can be considered analogous traits due to this convergent evolution.

The similarities in brains between octopi and other animals call into question how we define intelligence. Having the biggest brain is not always the best indicator. Many creatures can use tools, problem-solve, and have memories; just like humans can. I think this quote sums it up quite well:

“There is a lesson here about the ways that smart animals handle the stuff of their world. They carve it up into objects that can be remembered and identified despite changes in how those objects present themselves. This, too, is a striking feature of the octopus mind—striking in its familiarity and similarity to how we two-legged types make sense of our world.”

Peter Godfrey-Smith, Scientific American

So, what do you think? We've established that the octopus is smart despite being radically different from us. How should we define intelligence outside of an anthropocentric view?

#octopus#mollusks#cephalopod#invertabrates#brain#nervous system#evolution#convergent evolution#analogous traits#science

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Byebye probiotics?

February 2, 2023

Image credit: 1, 2, and 3

Everyone has been overwhelmed in the supplement aisle of a drug store or completely lost in a nutrition shop. Pills and powders are displayed that claim to cure various ailments. A popular item, especially for folks suffering from bacterial infections, is probiotics. After a course of antibiotics, patients may look to replenish the beneficial bacteria that were harmed in the process of killing the pathogenic bacteria in the infection. Many brands of probiotics boast the many millions of live bacteria their pills contain or that certain strains of bacteria will help manage urinary tract infections, IBS, or vaginal health. But are probiotics really doing what they claim?

Before we look at how probiotics work, it is important to understand why they seem necessary in the first place. Humans have existed with commensal bacteria living in their gut, mouth, vagina, urinary tract, skin, and lungs for thousands of years. These tiny single celled microbes have been permitted to stick around during the course of evolution because of the services they provide. Good bacteria are considered collaborators with their host. An immunology professor has called them “old friends.” For example, some produce essential B-vitamins for themselves and their human. The Human Microbiome project has identified that the gut microbiome contains at least 2,172 species of bacteria from twelve different phyla. In total, for every one human cell, there is one bacteria cell.

The diversity of the gut microbiome can be affected by many events over the course of one’s life as seen below.

Table 1 Factors responsible for shaping gut microbiota in various stages of life, adapted courtesy of NIH.

However, probiotics are not a perfect fix to disruptions to the gut microbiome. Researchers have not yet concluded that probiotics actually help. Studies are currently ongoing. Probiotics are also considered a supplement, not medication, and are therefore not regulated by the FDA. They are generally considered safe and recommended to be given a try to help with health issues. Probiotics are not recommended for people who are immunocompromised, going through chemotherapy, or recently had surgery. Risks include developing an infection or creating antibiotic resistant bacteria.

So what can you do? Studies have found that eating fermented food can increase microbiome diversity naturally, AND decrease inflammation. Foods such as “yogurt, kefir, fermented cottage cheese, kimchi and other fermented vegetables, vegetable brine drinks, and kombucha tea led to an increase in overall microbial diversity, with stronger effects from larger servings” according to one study.

The verdict is still out on whether probiotics are truly safe and effective. So, in the meantime, you will be finding me with kombucha in hand and some kimchi in my fridge.

Image credit: 1, 2, and 3

1 note

·

View note